This page covers the benefits and basic usage of Starlark configurations, Bazel's API for customizing how your project builds. It includes how to define build settings and provides examples.

This makes it possible to:

- define custom flags for your project, obsoleting the need for

--define - write

transitions to configure deps in

different configurations than their parents

(such as

--compilation_mode=optor--cpu=arm) - bake better defaults into rules (such as automatically build

//my:android_appwith a specified SDK)

and more, all completely from .bzl files (no Bazel release required). See the

bazelbuild/examples repo for

examples.

User-defined build settings

A build setting is a single piece of

configuration

information. Think of a configuration as a key/value map. Setting --cpu=ppc

and --copt="-DFoo" produces a configuration that looks like

{cpu: ppc, copt: "-DFoo"}. Each entry is a build setting.

Traditional flags like cpu and copt are native settings —

their keys are defined and their values are set inside native bazel java code.

Bazel users can only read and write them via the command line

and other APIs maintained natively. Changing native flags, and the APIs

that expose them, requires a bazel release. User-defined build

settings are defined in .bzl files (and thus, don't need a bazel release to

register changes). They also can be set via the command line

(if they're designated as flags, see more below), but can also be

set via user-defined transitions.

Defining build settings

The build_setting rule() parameter

Build settings are rules like any other rule and are differentiated using the

Starlark rule() function's build_setting

attribute.

# example/buildsettings/build_settings.bzl

string_flag = rule(

implementation = _impl,

build_setting = config.string(flag = True)

)

The build_setting attribute takes a function that designates the type of the

build setting. The type is limited to a set of basic Starlark types like

bool and string. See the config module

documentation for details. More complicated typing can be

done in the rule's implementation function. More on this below.

The config module's functions takes an optional boolean parameter, flag,

which is set to false by default. if flag is set to true, the build setting

can be set on the command line by users as well as internally by rule writers

via default values and transitions.

Not all settings should be settable by users. For example, if you as a rule

writer have some debug mode that you'd like to turn on inside test rules,

you don't want to give users the ability to indiscriminately turn on that

feature inside other non-test rules.

Using ctx.build_setting_value

Like all rules, build setting rules have implementation functions.

The basic Starlark-type value of the build settings can be accessed via the

ctx.build_setting_value method. This method is only available to

ctx objects of build setting rules. These implementation

methods can directly forward the build settings value or do additional work on

it, like type checking or more complex struct creation. Here's how you would

implement an enum-typed build setting:

# example/buildsettings/build_settings.bzl

TemperatureProvider = provider(fields = ['type'])

temperatures = ["HOT", "LUKEWARM", "ICED"]

def _impl(ctx):

raw_temperature = ctx.build_setting_value

if raw_temperature not in temperatures:

fail(str(ctx.label) + " build setting allowed to take values {"

+ ", ".join(temperatures) + "} but was set to unallowed value "

+ raw_temperature)

return TemperatureProvider(type = raw_temperature)

temperature = rule(

implementation = _impl,

build_setting = config.string(flag = True)

)

Defining multi-set string flags

String settings have an additional allow_multiple parameter which allows the

flag to be set multiple times on the command line or in bazelrcs. Their default

value is still set with a string-typed attribute:

# example/buildsettings/build_settings.bzl

allow_multiple_flag = rule(

implementation = _impl,

build_setting = config.string(flag = True, allow_multiple = True)

)

# example/BUILD

load("//example/buildsettings:build_settings.bzl", "allow_multiple_flag")

allow_multiple_flag(

name = "roasts",

build_setting_default = "medium"

)

Each setting of the flag is treated as a single value:

$ bazel build //my/target --//example:roasts=blonde \

--//example:roasts=medium,dark

The above is parsed to {"//example:roasts": ["blonde", "medium,dark"]} and

ctx.build_setting_value returns the list ["blonde", "medium,dark"].

Instantiating build settings

Rules defined with the build_setting parameter have an implicit mandatory

build_setting_default attribute. This attribute takes on the same type as

declared by the build_setting param.

# example/buildsettings/build_settings.bzl

FlavorProvider = provider(fields = ['type'])

def _impl(ctx):

return FlavorProvider(type = ctx.build_setting_value)

flavor = rule(

implementation = _impl,

build_setting = config.string(flag = True)

)

# example/BUILD

load("//example/buildsettings:build_settings.bzl", "flavor")

flavor(

name = "favorite_flavor",

build_setting_default = "APPLE"

)

Predefined settings

The Skylib library includes a set of predefined settings you can instantiate without having to write custom Starlark.

For example, to define a setting that accepts a limited set of string values:

# example/BUILD

load("@bazel_skylib//rules:common_settings.bzl", "string_flag")

string_flag(

name = "myflag",

values = ["a", "b", "c"],

build_setting_default = "a",

)

For a complete list, see Common build setting rules.

Using build settings

Depending on build settings

If a target would like to read a piece of configuration information, it can directly depend on the build setting via a regular attribute dependency.

# example/rules.bzl

load("//example/buildsettings:build_settings.bzl", "FlavorProvider")

def _rule_impl(ctx):

if ctx.attr.flavor[FlavorProvider].type == "ORANGE":

...

drink_rule = rule(

implementation = _rule_impl,

attrs = {

"flavor": attr.label()

}

)

# example/BUILD

load("//example:rules.bzl", "drink_rule")

load("//example/buildsettings:build_settings.bzl", "flavor")

flavor(

name = "favorite_flavor",

build_setting_default = "APPLE"

)

drink_rule(

name = "my_drink",

flavor = ":favorite_flavor",

)

Languages may wish to create a canonical set of build settings which all rules

for that language depend on. Though the native concept of fragments no longer

exists as a hardcoded object in Starlark configuration world, one way to

translate this concept would be to use sets of common implicit attributes. For

example:

# kotlin/rules.bzl

_KOTLIN_CONFIG = {

"_compiler": attr.label(default = "//kotlin/config:compiler-flag"),

"_mode": attr.label(default = "//kotlin/config:mode-flag"),

...

}

...

kotlin_library = rule(

implementation = _rule_impl,

attrs = dicts.add({

"library-attr": attr.string()

}, _KOTLIN_CONFIG)

)

kotlin_binary = rule(

implementation = _binary_impl,

attrs = dicts.add({

"binary-attr": attr.label()

}, _KOTLIN_CONFIG)

Using build settings on the command line

Similar to most native flags, you can use the command line to set build settings

that are marked as flags. The build

setting's name is its full target path using name=value syntax:

$ bazel build //my/target --//example:string_flag=some-value # allowed

$ bazel build //my/target --//example:string_flag some-value # not allowed

Special boolean syntax is supported:

$ bazel build //my/target --//example:boolean_flag

$ bazel build //my/target --no//example:boolean_flag

Using build setting aliases

You can set an alias for your build setting target path to make it easier to read on the command line. Aliases function similarly to native flags and also make use of the double-dash option syntax.

Set an alias by adding --flag_alias=ALIAS_NAME=TARGET_PATH

to your .bazelrc . For example, to set an alias to coffee:

# .bazelrc

build --flag_alias=coffee=//experimental/user/starlark_configurations/basic_build_setting:coffee-temp

Best Practice: Setting an alias multiple times results in the most recent one taking precedence. Use unique alias names to avoid unintended parsing results.

To make use of the alias, type it in place of the build setting target path.

With the above example of coffee set in the user's .bazelrc:

$ bazel build //my/target --coffee=ICED

instead of

$ bazel build //my/target --//experimental/user/starlark_configurations/basic_build_setting:coffee-temp=ICED

Best Practice: While it possible to set aliases on the command line, leaving them

in a .bazelrc reduces command line clutter.

Label-typed build settings

Unlike other build settings, label-typed settings cannot be defined using the

build_setting rule parameter. Instead, bazel has two built-in rules:

label_flag and label_setting. These rules forward the providers of the

actual target to which the build setting is set. label_flag and

label_setting can be read/written by transitions and label_flag can be set

by the user like other build_setting rules can. Their only difference is they

can't customely defined.

Label-typed settings will eventually replace the functionality of late-bound

defaults. Late-bound default attributes are Label-typed attributes whose

final values can be affected by configuration. In Starlark, this will replace

the configuration_field

API.

# example/rules.bzl

MyProvider = provider(fields = ["my_field"])

def _dep_impl(ctx):

return MyProvider(my_field = "yeehaw")

dep_rule = rule(

implementation = _dep_impl

)

def _parent_impl(ctx):

if ctx.attr.my_field_provider[MyProvider].my_field == "cowabunga":

...

parent_rule = rule(

implementation = _parent_impl,

attrs = { "my_field_provider": attr.label() }

)

# example/BUILD

load("//example:rules.bzl", "dep_rule", "parent_rule")

dep_rule(name = "dep")

parent_rule(name = "parent", my_field_provider = ":my_field_provider")

label_flag(

name = "my_field_provider",

build_setting_default = ":dep"

)

Build settings and select()

Users can configure attributes on build settings by using

select(). Build setting targets can be passed to the flag_values attribute of

config_setting. The value to match to the configuration is passed as a

String then parsed to the type of the build setting for matching.

config_setting(

name = "my_config",

flag_values = {

"//example:favorite_flavor": "MANGO"

}

)

User-defined transitions

A configuration transition maps the transformation from one configured target to another within the build graph.

Defining

Transitions define configuration changes between rules. For example, a request like "compile my dependency for a different CPU than its parent" is handled by a transition.

Formally, a transition is a function from an input configuration to one or more

output configurations. Most transitions are 1:1 such as "override the input

configuration with --cpu=ppc". 1:2+ transitions can also exist but come

with special restrictions.

In Starlark, transitions are defined much like rules, with a defining

transition()

function

and an implementation function.

# example/transitions/transitions.bzl

def _impl(settings, attr):

_ignore = (settings, attr)

return {"//example:favorite_flavor" : "MINT"}

hot_chocolate_transition = transition(

implementation = _impl,

inputs = [],

outputs = ["//example:favorite_flavor"]

)

The transition() function takes in an implementation function, a set of

build settings to read(inputs), and a set of build settings to write

(outputs). The implementation function has two parameters, settings and

attr. settings is a dictionary {String:Object} of all settings declared

in the inputs parameter to transition().

attr is a dictionary of attributes and values of the rule to which the

transition is attached. When attached as an

outgoing edge transition, the values of these

attributes are all configured post-select() resolution. When attached as

an incoming edge transition, attr does not

include any attributes that use a selector to resolve their value. If an

incoming edge transition on --foo reads attribute bar and then also

selects on --foo to set attribute bar, then there's a chance for the

incoming edge transition to read the wrong value of bar in the transition.

The implementation function must return a dictionary (or list of

dictionaries, in the case of

transitions with multiple output configurations)

of new build settings values to apply. The returned dictionary keyset(s) must

contain exactly the set of build settings passed to the outputs

parameter of the transition function. This is true even if a build setting is

not actually changed over the course of the transition - its original value must

be explicitly passed through in the returned dictionary.

Defining 1:2+ transitions

Outgoing edge transition can map a single input configuration to two or more output configurations. This is useful for defining rules that bundle multi-architecture code.

1:2+ transitions are defined by returning a list of dictionaries in the transition implementation function.

# example/transitions/transitions.bzl

def _impl(settings, attr):

_ignore = (settings, attr)

return [

{"//example:favorite_flavor" : "LATTE"},

{"//example:favorite_flavor" : "MOCHA"},

]

coffee_transition = transition(

implementation = _impl,

inputs = [],

outputs = ["//example:favorite_flavor"]

)

They can also set custom keys that the rule implementation function can use to read individual dependencies:

# example/transitions/transitions.bzl

def _impl(settings, attr):

_ignore = (settings, attr)

return {

"Apple deps": {"//command_line_option:cpu": "ppc"},

"Linux deps": {"//command_line_option:cpu": "x86"},

}

multi_arch_transition = transition(

implementation = _impl,

inputs = [],

outputs = ["//command_line_option:cpu"]

)

Attaching transitions

Transitions can be attached in two places: incoming edges and outgoing edges. Effectively this means rules can transition their own configuration (incoming edge transition) and transition their dependencies' configurations (outgoing edge transition).

NOTE: There is currently no way to attach Starlark transitions to native rules. If you need to do this, contact bazel-discuss@googlegroups.com for help with figuring out workarounds.

Incoming edge transitions

Incoming edge transitions are activated by attaching a transition object

(created by transition()) to rule()'s cfg parameter:

# example/rules.bzl

load("example/transitions:transitions.bzl", "hot_chocolate_transition")

drink_rule = rule(

implementation = _impl,

cfg = hot_chocolate_transition,

...

Incoming edge transitions must be 1:1 transitions.

Outgoing edge transitions

Outgoing edge transitions are activated by attaching a transition object

(created by transition()) to an attribute's cfg parameter:

# example/rules.bzl

load("example/transitions:transitions.bzl", "coffee_transition")

drink_rule = rule(

implementation = _impl,

attrs = { "dep": attr.label(cfg = coffee_transition)}

...

Outgoing edge transitions can be 1:1 or 1:2+.

See Accessing attributes with transitions for how to read these keys.

Transitions on native options

Starlark transitions can also declare reads and writes on native build configuration options via a special prefix to the option name.

# example/transitions/transitions.bzl

def _impl(settings, attr):

_ignore = (settings, attr)

return {"//command_line_option:cpu": "k8"}

cpu_transition = transition(

implementation = _impl,

inputs = [],

outputs = ["//command_line_option:cpu"]

Unsupported native options

Bazel doesn't support transitioning on --define with

"//command_line_option:define". Instead, use a custom

build setting. In general, new usages of

--define are discouraged in favor of build settings.

Bazel doesn't support transitioning on --config. This is because --config is

an "expansion" flag that expands to other flags.

Crucially, --config may include flags that don't affect build configuration,

such as

--spawn_strategy

. Bazel, by design, can't bind such flags to individual targets. This means

there's no coherent way to apply them in transitions.

As a workaround, you can explicitly itemize the flags that are part of

the configuration in your transition. This requires maintaining the --config's

expansion in two places, which is a known UI blemish.

Transitions on allow multiple build settings

When setting build settings that allow multiple values, the value of the setting must be set with a list.

# example/buildsettings/build_settings.bzl

string_flag = rule(

implementation = _impl,

build_setting = config.string(flag = True, allow_multiple = True)

)

# example/BUILD

load("//example/buildsettings:build_settings.bzl", "string_flag")

string_flag(name = "roasts", build_setting_default = "medium")

# example/transitions/rules.bzl

def _transition_impl(settings, attr):

# Using a value of just "dark" here will throw an error

return {"//example:roasts" : ["dark"]},

coffee_transition = transition(

implementation = _transition_impl,

inputs = [],

outputs = ["//example:roasts"]

)

No-op transitions

If a transition returns {}, [], or None, this is shorthand for keeping all

settings at their original values. This can be more convenient than explicitly

setting each output to itself.

# example/transitions/transitions.bzl

def _impl(settings, attr):

_ignore = (attr)

if settings["//example:already_chosen"] is True:

return {}

return {

"//example:favorite_flavor": "dark chocolate",

"//example:include_marshmallows": "yes",

"//example:desired_temperature": "38C",

}

hot_chocolate_transition = transition(

implementation = _impl,

inputs = ["//example:already_chosen"],

outputs = [

"//example:favorite_flavor",

"//example:include_marshmallows",

"//example:desired_temperature",

]

)

Accessing attributes with transitions

When attaching a transition to an outgoing edge

(regardless of whether the transition is a 1:1 or 1:2+ transition), ctx.attr is forced to be a list

if it isn't already. The order of elements in this list is unspecified.

# example/transitions/rules.bzl

def _transition_impl(settings, attr):

return {"//example:favorite_flavor" : "LATTE"},

coffee_transition = transition(

implementation = _transition_impl,

inputs = [],

outputs = ["//example:favorite_flavor"]

)

def _rule_impl(ctx):

# Note: List access even though "dep" is not declared as list

transitioned_dep = ctx.attr.dep[0]

# Note: Access doesn't change, other_deps was already a list

for other_dep in ctx.attr.other_deps:

# ...

coffee_rule = rule(

implementation = _rule_impl,

attrs = {

"dep": attr.label(cfg = coffee_transition)

"other_deps": attr.label_list(cfg = coffee_transition)

})

If the transition is 1:2+ and sets custom keys, ctx.split_attr can be used

to read individual deps for each key:

# example/transitions/rules.bzl

def _impl(settings, attr):

_ignore = (settings, attr)

return {

"Apple deps": {"//command_line_option:cpu": "ppc"},

"Linux deps": {"//command_line_option:cpu": "x86"},

}

multi_arch_transition = transition(

implementation = _impl,

inputs = [],

outputs = ["//command_line_option:cpu"]

)

def _rule_impl(ctx):

apple_dep = ctx.split_attr.dep["Apple deps"]

linux_dep = ctx.split_attr.dep["Linux deps"]

# ctx.attr has a list of all deps for all keys. Order is not guaranteed.

all_deps = ctx.attr.dep

multi_arch_rule = rule(

implementation = _rule_impl,

attrs = {

"dep": attr.label(cfg = multi_arch_transition)

})

See complete example here.

Integration with platforms and toolchains

Many native flags today, like --cpu and --crosstool_top are related to

toolchain resolution. In the future, explicit transitions on these types of

flags will likely be replaced by transitioning on the

target platform.

Memory and performance considerations

Adding transitions, and therefore new configurations, to your build comes at a cost: larger build graphs, less comprehensible build graphs, and slower builds. It's worth considering these costs when considering using transitions in your build rules. Below is an example of how a transition might create exponential growth of your build graph.

Badly behaved builds: a case study

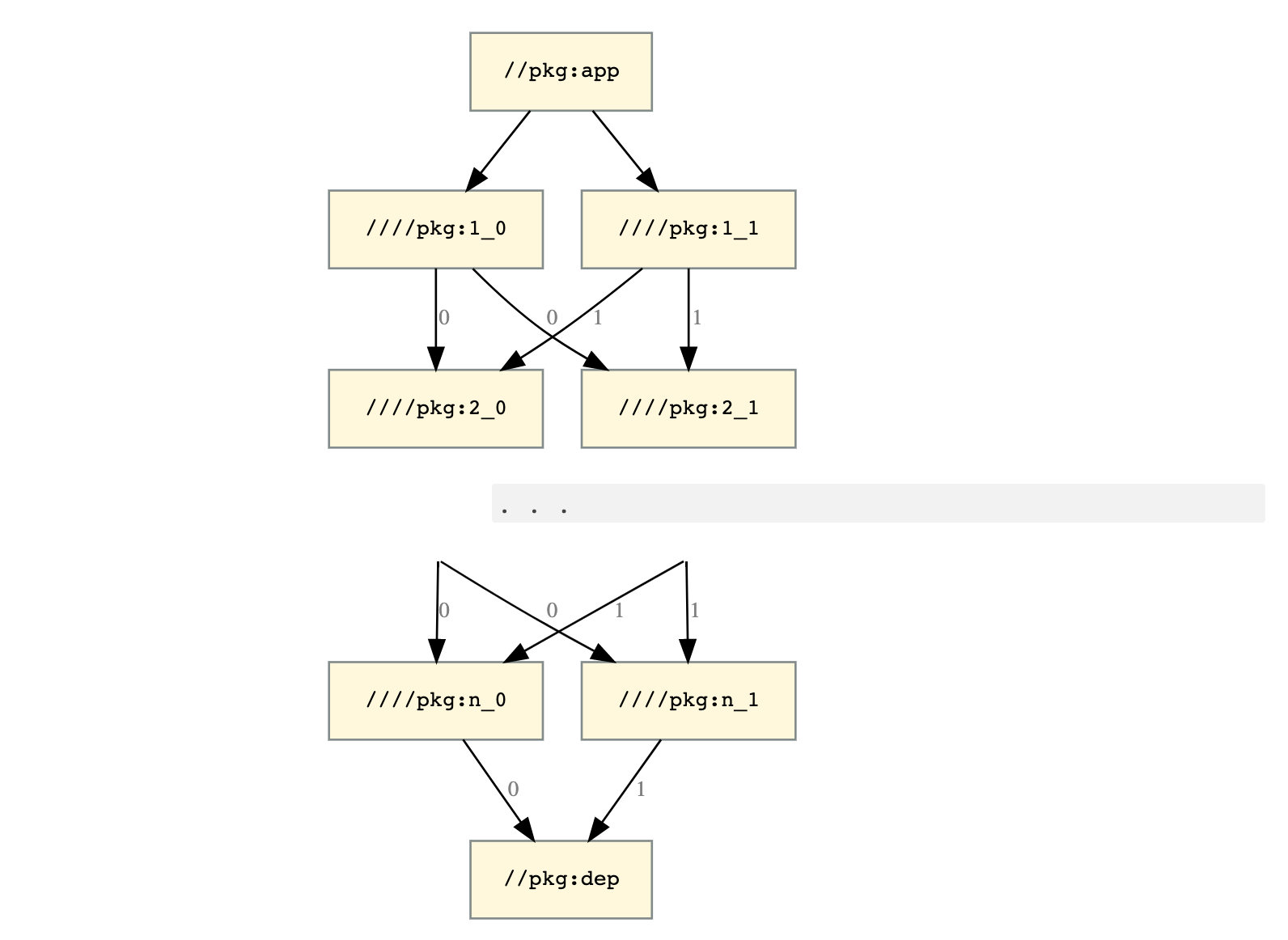

Figure 1. Scalability graph showing a top level target and its dependencies.

This graph shows a top level target, //pkg:app, which depends on two targets, a

//pkg:1_0 and //pkg:1_1. Both these targets depend on two targets, //pkg:2_0 and

//pkg:2_1. Both these targets depend on two targets, //pkg:3_0 and //pkg:3_1.

This continues on until //pkg:n_0 and //pkg:n_1, which both depend on a single

target, //pkg:dep.

Building //pkg:app requires \(2n+2\) targets:

//pkg:app//pkg:dep//pkg:i_0and//pkg:i_1for \(i\) in \([1..n]\)

Imagine you implement a flag

--//foo:owner=<STRING> and //pkg:i_b applies

depConfig = myConfig + depConfig.owner="$(myConfig.owner)$(b)"

In other words, //pkg:i_b appends b to the old value of --owner for all

its deps.

This produces the following configured targets:

//pkg:app //foo:owner=""

//pkg:1_0 //foo:owner=""

//pkg:1_1 //foo:owner=""

//pkg:2_0 (via //pkg:1_0) //foo:owner="0"

//pkg:2_0 (via //pkg:1_1) //foo:owner="1"

//pkg:2_1 (via //pkg:1_0) //foo:owner="0"

//pkg:2_1 (via //pkg:1_1) //foo:owner="1"

//pkg:3_0 (via //pkg:1_0 → //pkg:2_0) //foo:owner="00"

//pkg:3_0 (via //pkg:1_0 → //pkg:2_1) //foo:owner="01"

//pkg:3_0 (via //pkg:1_1 → //pkg:2_0) //foo:owner="10"

//pkg:3_0 (via //pkg:1_1 → //pkg:2_1) //foo:owner="11"

...

//pkg:dep produces \(2^n\) configured targets: config.owner=

"\(b_0b_1...b_n\)" for all \(b_i\) in \(\{0,1\}\).

This makes the build graph exponentially larger than the target graph, with corresponding memory and performance consequences.

TODO: Add strategies for measurement and mitigation of these issues.

Further reading

For more details on modifying build configurations, see:

- Starlark Build Configuration

- Full set of end to end examples